Anyone

who has read this blog for any length of time will know that I rely heavily

upon the writings and sayings of others. I frequently use the words that

another has said or written as a jumping off point for exploring my own

thoughts. Most of the time, I am confident that this is a fruitful method. Yet,

I am also aware of the pitfalls of such an approach and have often witnessed

problems with this technique in the writings of others; and so I know that it

must also exist in mine. The basic difficulty lies in the fact that by taking

one small snippet of a writer’s thoughts, we run the risk of missing their

meaning and perhaps interpreting their words in the opposite sense in which

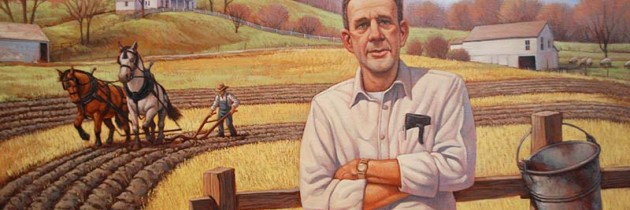

they were intended. For example, if one searches for quotes written by Wendell

Berry in his book, Jayber Crow, you

will find, online, a preponderance of quotes which support pessimism toward God

or toward his existence. Here is an example of an often used quote that, at

first glance, suggests that Berry is a proponent of atheism:

said, “if Jesus said for us to love our enemies – and He did say that,

didn’t He? – how can it ever be right to kill our enemies? And if

He said not to pray in public, how come we’re all the time praying in

public? And if Jesus’ own prayer in the garden wasn’t granted, what is

there for us to pray, except ‘thy will be done,’ which there’s no use praying

because it will be done anyhow?” . . . He said, “Have you any

more?”

said, for it had just occurred to me, “suppose you prayed for something

and you got it, how do you know how you got it? How do you know

you didn’t get it because you were going to get it whether you prayed for it or

not? So how do you know it does any good to pray? You would need

proof, wouldn’t you?”

proof.”

each other.

answers?”

cannot be given answers. You will have to live them out – perhaps a

little at a time.”

take?”

you live, perhaps.”

time.”

mystery,” he said. “It may take longer.”[1]

questions Wendell Berry’s character, Jayber Crow, asks are typical of one who

has had faith and then lost it. They suggest someone who is trying hard to

believe in Jesus, but just can’t do it. For those who like to draw quotes from

Wendell Berry to suggest agnosticism, this is sufficient to prove their point that, it is not rational to believe in a God who answers prayer and interacts

with His creation.

Crow says these words at a point that is one sixth of the way through the book.

One has to go a full two-thirds of the way through the book to see the answer

Jayber Crow gives himself. The answer, which shows a renewed faith in Jesus,

goes like this:

knew… why Christ’s prayer in the garden could not be granted. He had been

seeded and birthed into human flesh. He was one of us. Once He had become mortal,

He could not become immortal except by dying. That He prayed the prayer at all

showed how human He was. That He knew it could not be granted showed his

divinity; that He prayed it anyhow showed His mortality, His mortal love of

life that His death made immortal. . . .

the world, might that not be proved in my own love for it? I prayed to know in

my heart His love for the world, and this was my most prideful, foolish, and

dangerous prayer. It was my step into the abyss. As soon as I prayed it, I knew

that I would die. I knew the old wrong and the death that lay in the world.

Just as a good man would not coerce the love of his wife, God does not coerce

the love of His human creatures, not for Himself or for the world or for

another. To allow that love to exist fully and freely, He must allow it not to

exist at all. His love is suffering. It is our freedom and His sorrow. To love

the world as much even as I could love it would be suffering also, for I would

fail. And yet all the good I know is in this, that a man might so love this

world that it would break his heart.”[2]

are the words of a man who has found a renewal of his faith. These are the

words of someone who will trust Jesus. The point is, one must consider the

whole body of work before concluding the position of the author on this

particular issue. One small, or large, quote does not fully represent the

beliefs of Jayber Crow or, by extension, the beliefs of Wendell Berry. The

bottom line, for both writers and readers, is that we must not be lazy about

investigating the thoughts of an author. Truly substantiating a point may

require a good deal more reading than most of us choose to invest. Becoming

true scholars, knowledgeable readers, and connoisseurs of words will require a

good deal more outlay of time; but, as good scholars will know, the investment

is worth the reward.