Welcome to the world little man. You have already made a mark on my life. I have become a grandfather; you a grandson. We get to explore this relationship together and I have a surprisingly intense desire to excel at grand-fathering. From a biological perspective, you and I share one quarter of our DNA. I hope you got all of the good bits. Yet, even if you did get some of my less desirable traits, you need to know that biology is not destiny.

I am 52 and you are new-born. I pray that when you have experienced more of this life you will come to love life as much as I do. This world is so amazing and has so many things for you to learn and explore. I want to encourage you to never stop asking questions and never stop learning. I hope that you will become a student of the world and explore it with philosophy, science, mathematics, and theology. Never be afraid of truth; for all truth is God’s truth.

I pray that you will find the God who created this universe. I pray that you will have a long and happy life. I also pray that you will take risks in this life and never settle for the “safe” zone. Go ahead and make some mistakes; God knows that I have. I pray that whatever you may experience in this life, you will live it with peace, and joy, and bravery.

I pray that you will go for walks in the rain and the snow; get cold and wet but love the experience. I pray that you will fight for those smaller than you; poorer than you; sicker than you; more alone than you. I pray that you will enjoy life: play music, sing, write poetry, climb mountains, drink fine wine, enjoy rich food, appreciate a loaf of bread, find love, get your heart broken, and discover a good woman to love and marry.

I pray that you will appreciate the heritage of all of your ancestors who have gone before you. You have more than a little Celtic blood and even a Celtic name to go along with it. I pray that you will live with a sense of your own mortality, so that you might live well and appreciate this life. I pray that you will live life to the fullest every second of your existence in this world. I pray that you will look forward to a life beyond this one.

Welcome, Clayton Keith Smith (born November 6, 2012).

I saw a news story about a message in a bottle that had travelled approximately 4000 km from Gaspe, Quebec to East Passage, Ireland. The message, stuffed into a two litre plastic pop bottle had survived at sea for eight years and then been found by a nine year old boy. The girls who had set it adrift were twelve years old when they sent their note out to the world and, at twenty years old, were now surprised to hear that someone had finally found it.

This story caused me to think about why people send out a message in this fashion. The girls in Quebec had seen something on television that had made them want to try this; but what about other people? Why would anyone send a message by such an inefficient method of communication. Sting, in the song he did with “The Police,” says that it is about loneliness.

“Seems I’m not alone at being alone.” – Sting, “Message in a Bottle.”

The song suggests that many people have the feeling of being a lonely castaway looking for someone with whom to connect in a world filled with other lonely castaways.

“When you’re surrounded by all these people, it can be lonelier than when you’re by yourself. You can be in a huge crowd, but if you don’t feel like you can trust anyone or talk to anybody, you feel like you’re really alone.” – Fiona Apple

The movie, Message in a Bottle, starring Kevin Costner, suggests that the concept is about looking for that one person with whom we might romantically connect.

Perhaps the attraction of sending a message in a bottle is about desiring to find our own message from some distant place. Is it a desire for our own unique message that will guide our lives and give purpose for our future? Some have locked prayers in tiny bottles and sent them out on the waves, hoping, with little hope, that the message might be seen by some divine being.

A message in a bottle is a romantic concept. There are better ways to solve the loneliness; there are better ways to find romance; there are better ways to get a divine message. In a world of 8 billion people we need not cut ourselves off from each other or from God.

“We are all like foolish puppets who desiring to be kings; now lie pitifully crippled after cutting our own strings.” – Randy Stonehill

“Message In A Bottle”

(words and music by Sting)Just a castaway

An island lost at sea

Another lonely day

With no one here but me

More loneliness

Than any man could bear

Rescue me before I fall into despairI’ll send an SOS to the world

I’ll send an SOS to the world

I hope that someone gets my

Message in a bottle

Message in a bottleA year has passed since I wrote my note

But I should have known this right from the start

Only hope can keep me together

Love can mend your life

But love can break your heartI’ll send an SOS to the world

I’ll send an SOS to the world

I hope that someone gets my

I hope that someone gets my

I hope that someone gets my

Message in a bottle

Message in a bottleWalked out this morning

Don’t believe what I saw

A hundred billion bottles

Washed up on the shore

Seems I’m not alone at being alone

A hundred billion castaways

Looking for a homeI’ll send an SOS to the world

I’ll send an SOS to the world

I hope that someone gets my

I hope that someone gets my

I hope that someone gets my

Message in a bottle

Message in a bottleSending out an SOS

I am currently guest blogging at the Cosmos website. Please take a look at my review of Sigmund Brouwer’s great little book, Who Made the Moon?

Writers and bloggers of this world, will you hear the words of Annie Dillard? For those who have ears to hear, this is the life.

I do not so much write a book as sit up with it, as with a dying friend. During visiting hours, I enter its room with dread and sympathy for its many disorders. I hold its hand and hope it will get better. This tender relationship can change in a twinkling. If you skip a visit or two, a work in progress will turn on you.

A work in progress quickly becomes feral. It reverts to a wild state overnight. It is barely domesticated, a mustang on which you one day fastened a halter, but which now you cannot catch. It is a lion you cage in your study. As the work grows, it gets harder to control; it is a lion growing in strength. You must visit it every day and reassert your mastery over it. If you skip a day, you are, quite rightly, afraid to open the door to its room. You enter its room with bravura, holding a chair at the thing and shouting, “Simba!”

Living thus – with your lion tamer’s chair, your ax, your conference table, and your clothespin – you may excite in your fellow man not curiosity but profound indifference. It is not my experience that society hates and fears the writer, or that society adulates the writer. Instead my experience is the common one, that society places the writer so far beyond the pale that society does not regard the writer at all.1

As Dante wrote and Rodin inscribed, “All hope abandon ye who enter here.”

Dillard, Annie. The Writing Life. New York: Harper Perennial, 1990.

1 (Dillard 1990, 52, 53)

I read an interesting paragraph in an Annie Dillard book.

I admire those eighteenth century Hasids who

understood the risk of prayer. Rabbi Uri of Strelisk took sorrowful leave of

his household every morning because he was setting off to his prayers. He told

his family how to dispose of his manuscripts if praying should kill him. A

ritual slaughterer, similarly, every morning bade goodbye to his wife and

children and wept as if he would never see them again. His friend asked him

why. Because, he answered, when I begin I call out to the Lord. Then I pray,

“Have mercy on us.” Who knows what the Lord’s power will do to me in

the moment after I have invoked it and before I beg for mercy?

Dillard,

Annie. The Writing Life. New York: Harper Perennial, 1990, p. 8, 9.

I have a friend who works in criminal law in downtown Vancouver. Daily, he faces the “real world” of robbery, domestic abuse, drunk driving, murder, and many other indications of the brokenness of this world. My own experience with the real world comes from previous work in the ethics of a molecular genetics lab, years of experience as a leader in the church, and volunteer hours with an organization called Circles of Support and Accountability. He and I often discuss how to live in a world in which so much seems to be broken. That is one reason why we are presently reading Making the Best of It: Following Christ In The Real World by John G. Stackhouse, Jr. We read a chapter or two and get together to discuss the concepts we are learning from the book. (I would suggest that this is a great way to increase your learning from any particular book.)

The chapter we just discussed is about the theology and pragmatism of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It is an excellent chapter from which I learned a great deal about this remarkable man. He very much lived out his faith in the real world. He believed that his faith was to be lived for eternity but that it began in the here and now. Living in Germany during World War II as a Nazi resister, he knew that he lived in a fallen and broken world. Yet, he did not retreat from the problems of the world into some sort of, actual or virtual, church cloister. Nor did he set out to change society into a completely Christian world. Instead he chose to get his hands dirty and make the best of working in a world of light and darkness. Such thinking led Bonhoeffer to be part of the resistance against the Nazis and he even conspired with others to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Stackhouse suggests that “He did so, to be sure, only with the strongly conflicted sense that this was the thing God wanted him to do and yet he was doing something evil for which he needed – and hoped for – forgiveness.”1

Stackhouse also sees this type of thinking in other theologians such as C.S. Lewis and Reinhold Niebuhr and suggests that

We must press on, then, to conscientious and considered action. We seek forgiveness for the impurity of our motives and the evil results of our actions, but we must press on regardless to do what we can to increase justice and love. We must not be fastidious in a broken, heaving world and seek to keep our hands clean. We join with our God, who himself has dirt and blood on his hands as he does what good he can within this complicated system he has made and maintains – for the ultimate good of the world.2

On the other hand, Stackhouse, Lewis, Niebuhr, and Bonhoeffer are not kill-joys who see only the evil and brokenness of our world. Bonhoeffer was a man who loved life and wrote books, poetry, and music. He was incredibly balanced and was not prone to extremes. These words of his show a man who loved life and knew how to appreciate good gifts from the hand of God and embrace the joy of this world.

. . . within natural life, the joys of the body are a sign of the eternal joy that is promised human beings in the presence of God. . . . Unlike an animal shelter, a human dwelling is not intended to be only a protection against bad weather and the night, as well as a place to raise offspring. It is the space in which human beings may enjoy the pleasures of personal life in the security of their loved ones and their possessions. Eating and drinking serve not only the purpose of keeping the body healthy, but also the natural joy of bodily life. Clothing is not merely a necessary covering for the body, but is at the same time an adornment of the body. Relaxation not only serves the purpose of increasing the capacity for work, but also provides the body with the measure of rest and joy that is due to it. In its essential distance from all purposefulness, play is the clearest expression that bodily life is an end in itself. Sexuality is not only a means of procreation, but, independent of this purpose, embodies joy within marriage in the love of two people for each other.3

Stackhouse provides a new analysis of the traditional “categories of Christian involvement with society” presented in H. Richard Niebuhr’s book, Christ and Culture. The later chapters of Stackhouse’s book will provide a strategy for how we might live out a life of faith in a broken world that is still filled with joy and good gifts from God. I look forward to the rest of the book.

Stackhouse, John G., Jr. Making the Best of It: Following Christ In The Real World. New York: Oxford University Press , Inc., 2008.

1 (Stackhouse 2008, 157)

2 (Stackhouse 2008, 106, 107)

3 Dietrich Bonhoeffer as quoted in (Stackhouse 2008, 134, 135)

My friend Phil Reinders at Squinch reminded me of a great statement by G.K. Chesterton: “Here ends another day, during which I have had eyes, ears, hands and the great world around me. Tomorrow begins another day. Why am I allowed two?” Phil’s blog reminds us that we must ask the “Why me?” question in good times as well as tragic times. I often find myself asking the questions, “How did I win the lottery of being born in Canada rather than Haiti?” “Why did I get to live in the family I did with two good parents who loved me?” I have seen enough drug-addicted single parent situations (that cannot even be called family) to know that I might have been born into one such as that. Yes, these are just as difficult “why me?” questions. G.K. Chesterton asks why he is allowed two but when I do the math I can count more than 18,000 days in which I have had eyes, ears, hands, and much more.

I lost a good friend to cancer a year and a half ago. He was about 56 years old at the time; by today’s standards, too young to die. A few years before that I had a miraculous experience with the disappearance of a mass on the pons of my brain. Why did my friend die while I carried on living? These are important questions that will never be fully answered this side of heaven. But I still ask these questions and as I ask them I lift up a silent prayer of thanksgiving to the One who has made me with eyes, and ears, and hands, and a healthy pons, and with the ability to ask the “why me?” question in good times and in bad. In this season of Thanksgiving, my desire is to live a truly thankful life.

What do we mean when we say we are conscious? Can we explain consciousness by describing electro-chemical phenomena in the brain? How do we detect consciousness? I know that I am conscious but how can I be sure that other persons experience consciousness in a similar fashion to the way I sense it? This line of questioning led René Descartes to reduce his knowledge to the famous statement, “I think, therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum).

Are dogs conscious? Are the fleas on a dog’s back conscious? Could a computer ever attain consciousness? What if we were able to create human and mechanical hybrids; would they experience consciousness? This is a question often explored in science fiction characters such as “Data” in Star Trek The Next Generation or “The Doctor” in Star Trek Voyager.

David J. Chalmers, a philosopher of the mind, has made consciousness his area of study for many years. He says,

Consciousness poses the most baffling problems in the science of the mind. There is nothing that we know more intimately than conscious experience, but there is nothing that is harder to explain. All sorts of mental phenomena have yielded to scientific investigation in recent years, but consciousness has stubbornly resisted. Many have tried to explain it, but the explanations always seem to fall short of the target. Some have been led to suppose that the problem is intractable, and that no good explanation can be given.1

He calls this the hard problem of consciousness.

Why doesn’t all this information-processing go on “in the dark”, free of any inner feel? Why is it that when electromagnetic waveforms impinge on a retina and are discriminated and categorized by a visual system, this discrimination and categorization is experienced as a sensation of vivid red? We know that conscious experience does arise when these functions are performed, but the very fact that it arises is the central mystery. There is an explanatory gap (a term due to Levine 1983) between the functions and experience, and we need an explanatory bridge to cross it. A mere account of the functions stays on one side of the gap, so the materials for the bridge must be found elsewhere.2

What is that elsewhere? What bridges the gap between function and experience? Both atheists and Christians marvel at consciousness.

How can a three-pound mass of jelly that you can hold in your palm imagine angels, contemplate the meaning of infinity, and even question its own place in the cosmos? Especially awe inspiring is the fact that any single brain, including yours, is made up of atoms that were forged in the hearts of countless, far-flung stars billions of years ago. These particles drifted for eons and light-years until gravity and change brought them together here, now. These atoms now form a conglomerate- your brain- that can not only ponder the very stars that gave it birth but can also think about its own ability to think and wonder about its own ability to wonder. With the arrival of humans, it has been said, the universe has suddenly become conscious of itself. This, truly, it the greatest mystery of all.3

Is this one more place where we see the that science can take us far but cannot take us all the way to understanding? Is there a God factor in consciousness? Perhaps we can only understand consciousness as we understand the image of God in us.

Works cited:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consciousness

Chalmers, David J. “Facing Up To The Problem of Conciousness.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (1995): 200-219.

1 (Chalmers 1995, 200)

2 (Chalmers 1995, 204, 205)

3 V.S. Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us Human

Let me express my bias from the beginning. I am a hopeless romantic who believes in the love of one man for one woman for as long as both shall live. On October 2nd my wife and I celebrated our 33rd anniversary of dating. We have now been married 31 years and in that time we have seen many ups and downs and, like most couples, there were times when we wondered if we would be able to make it and keep the love alive. Yet, through the birth of three daughters, the loss of both of my wife’s parents, two university degrees, and too many stressors to count, we find that we still love being together.

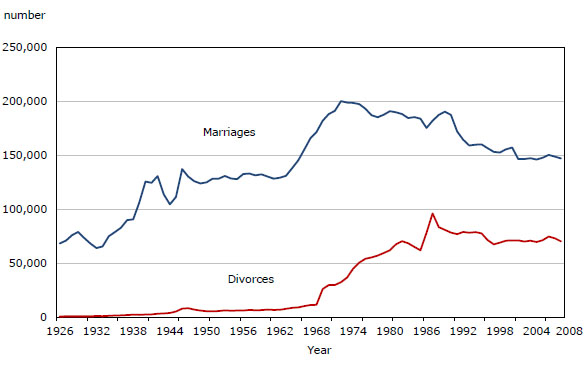

Recent statistics from the 2010 Canadian Census show that marriage is still a strong option for people in this country and that many marriages last for a long time. In 2008 it was estimated that 41% of marriages ended in divorce before the 30th year of marriage, an increase from 36% in 1998.1 Yet that still means that 59% of marriages last beyond 30 years. The following graph shows the raw number of marriages and divorces in Canada for the years 1926 to 2008. If we take the number of marriages in a given year, divide that number by the number of divorces in that same year, we can see some trends in the data. In 1926, there were 112.5 times as many marriages as divorces. In 1960 the ratio drops to 18.7 times as many marriages as divorces. 1970 sees a further drop to 6.3. By 1980 it is down to 3.1; dropping to its lowest in 1987 at 1.9. From 1988 to 2008, the ratio hovers around 2 (from 2.4 to 2.0). This means that twice as many people got married as got divorced in any one of those years. I will leave it to the reader to decide how optimistic or pessimistic we should be about such numbers and trends.

The benefits to both the married couple and the children of such long-term marriages are great. Of course not every marriage that lasts 30 or more years is a healthy one. We can all point to examples of long-term marriages that are seriously hurting; yet we need to celebrate marriages that truly succeed.

As a celebration of long-lasting love Mike Charko and I wrote a story-song about a love that lasted. We call it “Flowers.” You can listen to the recording while reading the lyrics.

Flowers

(Words and lyrics by Mike Charko and Keith Shields 2012 SOCAN)

His heart was smitten by this sweet young girl

She was the one who could rock his world

He didn’t quite know the right protocol

But sure she was the best of all

He brought her the perfect gift

He brought her flowers

When he didn’t know what to do

He brought her flowers

To prove his love was true

When the road was rough

Or when times were good

When he knew his love could never be enough

But this love was all he knew

So he brought her flowers

She said I’m not sure about marrying you

This world is big and there is so much to do

Afraid he’d lost her to another goal

So he looked down inside his soul

And he promised with all of his might

And he brought her flowers

When he didn’t know what to do

He brought her flowers

To prove his love was true

When the road was rough

Or when times were good

When he knew his love could never be enough

But this love was all he knew

So he brought her flowers

When she brought him their son

And three more girls

He had all he could want in this world

When the kids moved out

And she was blue

He knew what he had to do

He brought her flowers

When he didn’t know what to do

He brought her flowers

To prove his love was true

When the road was rough

Or when times were good

When he knew his love could never be enough

But this love was all he knew

So he brought her flowers

The last time I saw him he was all alone

His eyes looked tired and his beard had grown

He walked along with a shuffling stroll

As he headed on down the road

To a plot where a gravestone stood

And he brought her flowers

When he didn’t know what to do

He brought her flowers

To prove his love was true

When the road was rough

Or when times were good

When he knew his love could never be enough

But this love was all he knew

So he brought her flowers

He brought her flowers

1 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2012001/article/11634-eng.htm

The words of the song “Handmade” by Jimmy Rankin say, “Everywhere I go everything’s plastic.” I understand these words. It is all too easy to find pretense and masque all around us. Authenticity is something for which we long. We long for it in the music industry, in business, in spirituality, and in our relationships with our neighbours. We long for authenticity in our families, in our marital relationships, and in our friendships. We long for authenticity in every aspect of life.

When my wife and I travelled on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia we saw a level of authenticity in music that is rare to find. Many cafes, pubs, and restaurants had live music. Often it was one person on fiddle and one person on a piano. The two would play music they loved and occasionally sing. Much ad lib, improvisation, and experimentation would occur. One got the impression that you were looking over the shoulders of a couple of friends who had just sat down around the family piano. Other times it might be one or two people with a guitar and other instruments and perhaps a bit of step dancing or highland dancing thrown in. The contrast to highly produced radio music coming out of Toronto and Los Angeles was stark. This East Coast music felt very authentic.

Music is simply one example of an area in which we desire to see a greater degree of authenticity. Most of us would be happy to see a much greater degree of genuineness in all aspects of life. Where does such authenticity start? Of course, it starts with me. If I desire for others to be genuine with me I must necessarily be genuine with them. Perhaps that also means that I must become more comfortable with the person I am. Can I even take off the masque and look in my own mirror? If I want the world to give me something real – something handmade – something I can taste – it must start with introspection and analysis of myself. Only when I understand who I am will I be able to reveal that to others around me. Only then will I encourage this in others.

Enjoy these great lyrics by a great singer songwriter. You can listen to the song here.

Handmade (Lyrics and music by Jimmy Rankin and Tim Thorney)

Everywhere I go everything’s plastic

Everywhere I turn it’s all the same

I’m makin’ my way through the smoke and the ashes

It’s out of the fire and into the flameGive me something that is real

Give me something I can taste

Show me someone who can feel

I’m sick and tired of this place

But everybody must get paid

Give me something handmade

HandmadeHave we lost our style in the face of fashion?

Have we lost the need and the will to care?

Something’s gone nobody’s asking

Seems the more I look it’s nowhereGive me something that is real

Give me something I can taste

Show me someone who can feel

I’m sick and tired of this place

But everybody must get paid

Give me something handmade

HandmadeThese are the days of concrete and steel

This is the circus with the dancing clown

Hear the thundering roar roll over the border

These are the days when it all comes downGive me something that is real

Give me something I can taste

Show me someone who can feel

I’m sick and tired of this place

But everybody must get paid

Give me something handmade

Handmade

Give me something handmade

Handmade