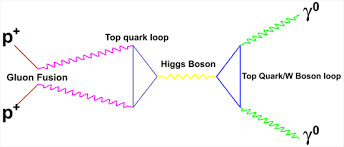

Higgs-Bosons, Up, Down, Charmed, and Strange Quarks,

Anti-matter, Dark-Matter, and Light as both wave and particle – at one and the

same time. These are the present realities of physics which even the public has

come to accept as incomprehensible, but real. How can one begin to understand a

universe that contains this many uncertainties, paradoxes, and seeming

impossibilities? Yet, this is what our contemporary mind has been trained to do

by the realities of our physical world. It did not start with Albert Einstein,

but his descriptions of the Theory of Relativity did much to train the world to

believe two contradictory truths at once. This is one of the hallmarks of our

post-modern culture and this influences philosophy and theology as well as

science. As Alistair McGrath puts it.

Anti-matter, Dark-Matter, and Light as both wave and particle – at one and the

same time. These are the present realities of physics which even the public has

come to accept as incomprehensible, but real. How can one begin to understand a

universe that contains this many uncertainties, paradoxes, and seeming

impossibilities? Yet, this is what our contemporary mind has been trained to do

by the realities of our physical world. It did not start with Albert Einstein,

but his descriptions of the Theory of Relativity did much to train the world to

believe two contradictory truths at once. This is one of the hallmarks of our

post-modern culture and this influences philosophy and theology as well as

science. As Alistair McGrath puts it.

For an orthodox Christian theologian,

the doctrine of the Trinity is the inevitable outcome of intellectual

engagement with the Christian experience of God; for the physicist, equally

abstract and bewildering concepts emerge from wrestling with the world of

quantum phenomena. But both are committed to sustained intellectual engagement

with [these] phenomena, in order to derive and develop theories or doctrines

which can be said to do justice to them, preserving rather than reducing them.

Both the sciences and religion may therefore be described as offering

interpretations of experience. (McGrath, 1998, p. 88)[1]

the doctrine of the Trinity is the inevitable outcome of intellectual

engagement with the Christian experience of God; for the physicist, equally

abstract and bewildering concepts emerge from wrestling with the world of

quantum phenomena. But both are committed to sustained intellectual engagement

with [these] phenomena, in order to derive and develop theories or doctrines

which can be said to do justice to them, preserving rather than reducing them.

Both the sciences and religion may therefore be described as offering

interpretations of experience. (McGrath, 1998, p. 88)[1]

The Bible speaks of the Creator God who is the same yesterday,

today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8); the canon of the Bible has now been

established for many centuries and will not be changed; but theology has and

will change. Science, philosophy, and theology must change, as they are interpretations

of experience. God remains the same, but humans have passed knowledge and

experience from one generation to another, slowly building a base of wisdom and

information that allows us to relate to our physical, philosophical, and

theological world. Humans, as a collective, know much more about the universe

today than we did prior to God’s Abrahamic covenant with his people. Humans are

not the same people today as those who interacted with him in the Middle-East

or African deserts of those times. So, the unchanging God has chosen to change

the way in which he has interacted with humans. First, he chose a way to

interact with those who lived in the days of Adam and others before the Abrahamic Covenant. The details of this interaction are sparse and hard to ascertain, but

clearly different from his covenant with Abraham. Then, there are all those who

lived under the covenant of Abraham, as described in Genesis 12:2 and 3.

today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8); the canon of the Bible has now been

established for many centuries and will not be changed; but theology has and

will change. Science, philosophy, and theology must change, as they are interpretations

of experience. God remains the same, but humans have passed knowledge and

experience from one generation to another, slowly building a base of wisdom and

information that allows us to relate to our physical, philosophical, and

theological world. Humans, as a collective, know much more about the universe

today than we did prior to God’s Abrahamic covenant with his people. Humans are

not the same people today as those who interacted with him in the Middle-East

or African deserts of those times. So, the unchanging God has chosen to change

the way in which he has interacted with humans. First, he chose a way to

interact with those who lived in the days of Adam and others before the Abrahamic Covenant. The details of this interaction are sparse and hard to ascertain, but

clearly different from his covenant with Abraham. Then, there are all those who

lived under the covenant of Abraham, as described in Genesis 12:2 and 3.

“I will make you into a great nation,

and I will bless you;

I will make your name great,

and you will be a blessing.

I will bless those who bless you,

and whoever curses you I will curse;

and all peoples on earth

will be blessed through you.”

and I will bless you;

I will make your name great,

and you will be a blessing.

I will bless those who bless you,

and whoever curses you I will curse;

and all peoples on earth

will be blessed through you.”

Next, there is the Mosaic Covenant, described in Exodus 19,

in which God reminds his people of their obligation to obey all that he has

commanded them in the Law, and the people respond with, “All that the Lord has

spoken we will do!”

in which God reminds his people of their obligation to obey all that he has

commanded them in the Law, and the people respond with, “All that the Lord has

spoken we will do!”

The next change that occurs within the way in which God

interacts with his people is the Incarnation. In this covenant, God himself

steps into history, biology, and physics, in the form of Jesus Christ,

Immanuel. The Good News of the New Testament is the covenant between God and

people who choose to follow Jesus, who is the Lord. As far as we know, this

represents the last iteration of God’s interaction with his people, before the

final judgement and the renewal of all in the definitive Kingdom of God.

interacts with his people is the Incarnation. In this covenant, God himself

steps into history, biology, and physics, in the form of Jesus Christ,

Immanuel. The Good News of the New Testament is the covenant between God and

people who choose to follow Jesus, who is the Lord. As far as we know, this

represents the last iteration of God’s interaction with his people, before the

final judgement and the renewal of all in the definitive Kingdom of God.

Again, I need to remind myself and my readers that this is

not about God changing, the Bible changing, or the cultural perspective of

humans changing. This is about the information, wisdom, and experience of

humans that shape how God chooses to interact with his created beings. As humans

grow, mature, and advance in technology, God chooses to interrelate to us in

new ways.

not about God changing, the Bible changing, or the cultural perspective of

humans changing. This is about the information, wisdom, and experience of

humans that shape how God chooses to interact with his created beings. As humans

grow, mature, and advance in technology, God chooses to interrelate to us in

new ways.

The previous discussion about how God has chosen to relate

to humans may give us cause to pause in our desire to be completely and

definitively correct in our assessments of anything in life. If science has the

potential to discover new things that shape the way we view life, then theology

and our understanding of the Bible can and will change as humans mature and

change. We should not be too quick to decide that we have the last word on any

given topic, theological or secular. Some new fact or feature may be discovered

which requires an attenuation, correction, or confirmation of our assessment.

In other words, on some given topic, we might be wrong.

to humans may give us cause to pause in our desire to be completely and

definitively correct in our assessments of anything in life. If science has the

potential to discover new things that shape the way we view life, then theology

and our understanding of the Bible can and will change as humans mature and

change. We should not be too quick to decide that we have the last word on any

given topic, theological or secular. Some new fact or feature may be discovered

which requires an attenuation, correction, or confirmation of our assessment.

In other words, on some given topic, we might be wrong.

McGrath, A. E. (2007). Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes, and the

Meaning of Life. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Meaning of Life. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

[1]

Alister McGrath, Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life (Malden:

Blackwell Publishing, 1998), 88.

Alister McGrath, Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life (Malden:

Blackwell Publishing, 1998), 88.