“What does it mean to be

alive? To think, to feel, to love and to envy? André Alexis explores all of

this and more in the extraordinary Fifteen Dogs, an insightful and

philosophical meditation on the nature of consciousness. It’s a novel filled

with balancing acts: humour juxtaposed with savagery, solitude with the

desperate need to be part of a pack, perceptive prose interspersed with playful

poetry. A wonderful and original piece of writing that challenges the reader to

examine their own existence and recall the age old question, what’s the meaning

of life?”[1]

alive? To think, to feel, to love and to envy? André Alexis explores all of

this and more in the extraordinary Fifteen Dogs, an insightful and

philosophical meditation on the nature of consciousness. It’s a novel filled

with balancing acts: humour juxtaposed with savagery, solitude with the

desperate need to be part of a pack, perceptive prose interspersed with playful

poetry. A wonderful and original piece of writing that challenges the reader to

examine their own existence and recall the age old question, what’s the meaning

of life?”[1]

This quote reminds us that authors and

screenwriters have been writing about consciousness and the essence of life for

a very long time. Fifteen Dogs, by

Andre Alexis, which recently won the 2015 Scotiabank Giller Prize is a significant

addition to the genre. If you add to this the concept of artificial

intelligence (AI), as a related subject, the list of stories grows even longer.

A few key questions continue to be asked. Would it ever be possible to create

life? How would one know if life had been created? Would it ever be possible to

create consciousness? How would one know if consciousness had been created? Would

it be possible to create an artificial intelligence that was indistinguishable

from a human? If one were able to do this, would it indeed be human? What does

it mean to be human? Is there a need to protect humans from their own

creations?

screenwriters have been writing about consciousness and the essence of life for

a very long time. Fifteen Dogs, by

Andre Alexis, which recently won the 2015 Scotiabank Giller Prize is a significant

addition to the genre. If you add to this the concept of artificial

intelligence (AI), as a related subject, the list of stories grows even longer.

A few key questions continue to be asked. Would it ever be possible to create

life? How would one know if life had been created? Would it ever be possible to

create consciousness? How would one know if consciousness had been created? Would

it be possible to create an artificial intelligence that was indistinguishable

from a human? If one were able to do this, would it indeed be human? What does

it mean to be human? Is there a need to protect humans from their own

creations?

Ex

Machina, a 2015 movie, focused on robots that were

designed to be indistinguishable from humans. Even as the Giller Prize judges

ruminate upon the words, “to think, to feel, to love, to envy,” so also do the

writers of this screenplay. Another film, Her

(2013), grappled with the concept of an intelligence that resided in the

hardware of a computer and went on to develop feelings. Eventually the OS being was capable of learning beyond

the capabilities of the ones who had created it and exhibited feelings for

humans and other OS entities. Although a much older discussion, I, Robot, a 1950 collection of

short-stories by famed Sci-Fi writer Isaac Asimov, asked questions about the

safety of creating artificial intelligences and constructed the “Three Laws of

Robotics.”

Machina, a 2015 movie, focused on robots that were

designed to be indistinguishable from humans. Even as the Giller Prize judges

ruminate upon the words, “to think, to feel, to love, to envy,” so also do the

writers of this screenplay. Another film, Her

(2013), grappled with the concept of an intelligence that resided in the

hardware of a computer and went on to develop feelings. Eventually the OS being was capable of learning beyond

the capabilities of the ones who had created it and exhibited feelings for

humans and other OS entities. Although a much older discussion, I, Robot, a 1950 collection of

short-stories by famed Sci-Fi writer Isaac Asimov, asked questions about the

safety of creating artificial intelligences and constructed the “Three Laws of

Robotics.”

1. A robot may not injure a human being or,

through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by

human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence

as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.[2]

as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.[2]

Nathan,

the brilliant billionaire CEO of Bluebook, in the movie Ex Machina, would have saved himself a lot of trouble if he had

read these principles of robotics and built them into his own version of the

positronic brain.

the brilliant billionaire CEO of Bluebook, in the movie Ex Machina, would have saved himself a lot of trouble if he had

read these principles of robotics and built them into his own version of the

positronic brain.

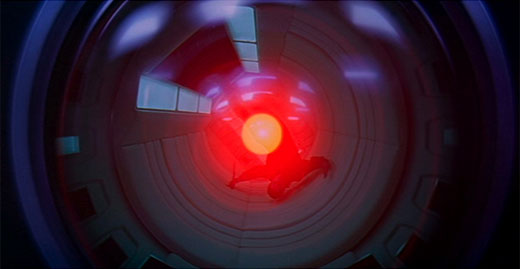

Arthur

C. Clarke, in his novel 2001: A Space Odyssey, wrote about a renegade computer that managed to outsmart a team of

astronauts on a mission to one of the moons of Jupiter. The novel became a

stunning movie in 1968 under the direction of Stanley Kubrick. The murderous

computer, HAL 9000, considers himself a conscious entity and finds that he is

afraid when he begins to lose his ability to think.[3]

C. Clarke, in his novel 2001: A Space Odyssey, wrote about a renegade computer that managed to outsmart a team of

astronauts on a mission to one of the moons of Jupiter. The novel became a

stunning movie in 1968 under the direction of Stanley Kubrick. The murderous

computer, HAL 9000, considers himself a conscious entity and finds that he is

afraid when he begins to lose his ability to think.[3]

In

the Genesis creation account, we read that “God created human beings

in his own image. In the image of God he created them; male and

female he created them;” and for centuries, theologians and philosophers have

been seeking to understand the nature of this imago dei (image of God). We have much yet to learn, but I am

convinced that the beginning of wisdom is to take seriously this concept. The

more we understand the nature of this image, the greater we will comprehend

what it is that makes us truly human. God is a Creator and we are creators. God

is in relationship and calls us to be in relationship with him and with others.

God is a communicator and we are communicators. God is truth and calls us to

truth. God is love and calls us to be love as well.

the Genesis creation account, we read that “God created human beings

in his own image. In the image of God he created them; male and

female he created them;” and for centuries, theologians and philosophers have

been seeking to understand the nature of this imago dei (image of God). We have much yet to learn, but I am

convinced that the beginning of wisdom is to take seriously this concept. The

more we understand the nature of this image, the greater we will comprehend

what it is that makes us truly human. God is a Creator and we are creators. God

is in relationship and calls us to be in relationship with him and with others.

God is a communicator and we are communicators. God is truth and calls us to

truth. God is love and calls us to be love as well.

Whatever

the final answers regarding the image of God, we need not fear the AI

apocalypse that has been depicted in so many of the stories, movies and

writings in our majority culture. God, who created us from the dust of the earth,

and created the dust before that, is the ultimate creator and sustainer. He is

in control of all life and has set humans to be stewards of His creation. Even

as we struggle to achieve this assignment, and sometimes pursue short-cuts to

cleaning up the messes we have made, the God of the universe watches us and

engages us with gracious concern. May His will be done; for this is what it

means to be alive.

the final answers regarding the image of God, we need not fear the AI

apocalypse that has been depicted in so many of the stories, movies and

writings in our majority culture. God, who created us from the dust of the earth,

and created the dust before that, is the ultimate creator and sustainer. He is

in control of all life and has set humans to be stewards of His creation. Even

as we struggle to achieve this assignment, and sometimes pursue short-cuts to

cleaning up the messes we have made, the God of the universe watches us and

engages us with gracious concern. May His will be done; for this is what it

means to be alive.

[1] CBC Books; CBC website; http://www.cbc.ca/books/2015/11/who-will-win-the-2015-scotiabank-giller-prize.html